Dear Lola and Abeera,

Thank you so much for the invitation to read last Friday. I feel like you, the readers, the friends I met and made - the fullness of the space you created - has been with me all week.

You asked me to send you my reading for your archive and I wanted to share that, along with what I remember, and what I felt.

Do you remember when Latifa read on Friday? I remember that at the beginning as she held her papers, her hands were shaking but when she read, her strong voice didn’t quiver once. It was as clear and true throughout as it was in the section where she closed her eyes as if in meditation, lost in song or dreaming (a prayer, I think, that her father sent her, I’m not sure, but I will ask her). In her reading she talked about experiencing pain in her body, and her neighbour sharing her body work practice with her, helping her to reorient her relationship with it. Throughout the reading Latifa talks about the weight of the world as she had been experiencing it: the Kahramanmaras earthquakes, the murder of Brianna Ghey, along with the ways that these losses bleed into the shape of her everyday. The ways anger rises when an Imam suggests a form of individualised acceptance without structural accountability, or the ways that our political longings can be tinged with doubtfulness as we grieve.

Her piece reminded me of your work Lola, on the imagination, and the ways that this is layered and shaped by what we have been gifted, not gifted, what we have known or are still to know. At the end of Latifa’s text she describes flying - arms outstretched riding through London streets on her bike - and her body free from pain. She rides between the space between two buses, as big as she can be in the space that has opened up. In a city that sometimes isolates us, between two structures that are hard, she finds solitude but not loneliness - finding company in the hundreds of red lights that she sees twinkling down the road.

Both yours Lola, and Latifa’s reading reminded me of a practice which I have been trying, where when my mind is racing and I feel weight on my shoulders that make me hunch and close off from the world, I track my body for a place that feels best. Here I turn my attention to what it might feel like if that good feeling could spread open in the way that the pain that closed me has; track what it might feel like to open out the places that pain constricts.

Friday made me want to map this practice onto my life, training my critical eye to turn not to the places where I feel most uncomfortable but to feel - with my whole body - the places where I feel most held. I felt it when I found you both behind the ticket desk on Friday and you greeted me with stickers, a hug and cigarettes. Then again when I told you Lola about my trip to Berlin, about a weird work thing that had happened - as I was speaking to track my discomfort you helped me track the bit that felt good. You showed me that I was finding the edges of the spaces I’d been in; its (in)ability to hold what I needed.

I am learning it takes practice, in these worlds we live/l(earn)/work in that reflect the shitty world we want to change, to track where our desires live, to practise placing ourselves more carefully in relation to them. I feel grateful for this lesson, possible only through the experience of being invited into spaces where I don’t have to be careful (on guard) but that could be careful with me.

The careful space you made taught me these profound things but it also filled me with knowledge that wasn’t heavy, but effervescent with joy and possibility. When I read my piece, I remember so much the way that people laughed in places I didn’t think they would. There was the bit where I talked about Leena striking (me) and the next line I meant so seriously, but because of how everyone laughed with me, I laughed as I read it. I know now, I have felt! that if a space is held, inside or outside of us the heaviest of loads can feel effortless, light and joyous - these things can coexist and must!

Like when Sita read about risk, she told us of course the reality of stopping traffic at an action is truly risky, but it's all relative, because when your mind is racing with completing an action, the worst has happened and you’ve been arrested, it takes its place alongside the risk you took when you borrowed your mum’s coat without asking. I learnt also, that when you have freed yourself to read with the tactility that Ama does, you can also let yourself have a margherita before you go up on stage. And Sarah taught me that being an artist with integrity can be fun! It means you can write a honey roast for those you love, but also use your skills to turn the sour taste of bad (so bad) political pontification that you have been subjected to into an urge to write that is so sharp it will cut through dread that is not yours with ease. And you know at the end when Sarona’s baba interrupted the text on her phone by calling? She let him enter her reading, welcomed him in, reminding us that our words are never found alone, they are always living, never fixed on the page, always in relation with the people and places that have made us, the ones we will turn into, and the ones we are still to find.

I learnt that a stage does not have to create a dominant voice, that is uplifted to blind us with their brilliance. It can bathe someone in light so completely, so that they are totally seen. Each person’s voice can be so different but so clear, so true to them. When we read, laugh and dance, we imagine a space that can hold simultaneity: where multiple strategies are attempted, understood and held. The stage can be a stage but the audience doesn’t have to be passively served, or engaged, with the right relation they are callers, responders, a chorus. This kind of raising (razing?) cannot interrupt relation; it simply helps us to uplift the person who needs to speak, needs to write, who must dig deep and who cannot help but try to resist.

Please do more soon,

With love

Jemma (and Leena)

For Leena, on the day of your first strike

36 years before the day of your first strike, in 1986, just a few stops on the bus away, there were other strikes that lay on top of still other strikes.These strikes aren’t included in the numbers they quote when they say that that year, in 1986 - a year after the miners were defeated - the numbers of days lost to strike action in Britain

was

at its lowest,

in almost 20 years.

The uncounted strikes included the refusals of other minors - school kids, like you, whose labour was not counted and whose compliance history assumed.

In January that year, one hundred Bengali students walked out of Morpeth secondary. Sick of the racism at their school, and at others in the area:

they went on strike.

Setting up an antiracist school in Oxford House, just off Bethnal Green Rd, they got ready to learn and teach things they lacked and knew they needed.

It's hard to know what their demands were though, because it wasn’t them who decided what to record, how to record it and what it meant. The Inner London Education Authority managed who spoke on camera to whom, and what was recorded and reported, archived and saved.

Still,

radical teachers collected what was there; recordings, clippings, flyers and photos. Teachers like Marina Foster, a South African refugee and Ken Jones a member of the Socialist Teachers Alliance collected essays like one where a student rages against the holes in the education they were supposed to gratefully turn up for:

‘does it prepare me’ they ask ‘or help me tackle the blatant and insidious forms of racism that, I am afraid to say, I will invariably encounter?’These teachers and educators donated these archives to the local authority, but at some point it was decided that certain records should be sealed. Because they named children - minors - who might have been perpetrators, or might have been victims.

They sealed the lips of these records,

That might speak a history of protest,

for 100 years.

It was only when a nosy archivist looked through them, that they realised that no one was named: that the lips could be unsealed so now the protest could speak, but its voice had been interrupted, it trailed off …

But even before then, there were kids who resisted, right near the streets where we live.

SKAN was a group of Hackney teenagers, School Kids against Nazis who organised against the racism of the National Front and the influence it had on the children who internalised it.

On a video on youtube the kids talk about racism and resisting it Right there in school, nip it in the bud they say.

They hand out badges and flyers,

They chant.

We are Black we are White we are Dynamite!Strike as in the strike before an explosion,

A show of force,

School Kids against Nazis.

***

On the day of your first strike, we went to two picket lines.

I tried to find the traces of these histories when we went to your school. But when we got there, it was like it had disappeared. All I found was a shrine of pastries from Gail’s bakery and a few parents who asked teachers if they were getting paid that day.

They apologised they had to go, they had to work.

Politely, a stroke not a strike, no fire but

They supported they supported they supported.

The children played, it was a beautiful day,

The sky was blue blue blue blue.

The strike they made was with a ball,

No aim just free, these kids struck and struck and struck.

It’s so nice the parents said, that the children can play on the street,

They never get to do that,

So free free free.

We support, we support, we support.

And all I could think about was the ball flying into the road, a child going after it and the bus driver, the ambulance driver the bin collectors who supported through striking their horns, would have to swerve from this other spinning strike, this game, unprotected, to protect others free to strike with a game and not a lost paycheck, while their parents still earned and redistributed their wealth through £5 pastries that would probably go mouldy.

At this picket line you found a sign, the one in the picture I took.

It was on soft cardboard, letters drawn with a thick brush by an adult, someone’s mum, strokes not strikes, a blue and purple ombre,

like a bruise.

It said

SOMEWHERE INSIDE ALL OF US IS THE POWER TO CHANGE THE WORLD

I make you stand and take your picture but it feels wrong. Of course I want you to KNOW that, but not like this at a strike that is not a strike exactly but like a simulation of the Whatsapp group where parents organise ski trips, mum’s night at the pub and swap Mini Rodini lost property.

The romance of the statement softens in my hands, unspecific, well-meaning; tender, also like a bruise; and I remember that a real bruise forms when vessels break and leak blood under the skin.

But these vessels that carry what a body needs to the places that it needs it, don’t break gently.

These ruptures appear after force.

A strike.

At the second picket, which is mine,

you are handed another sign,

a firmer one this time,

with a handle,

drawn by someone’s child.

In this one there is no bleeding heart, no wound, only a clear demand

WE WANT MONEY GIVE US OUR MONEY

The older girls teach you the call, give you the materials, the rewards, the motivation, (Homemade cookies). Teach you to say confidently “Support the strike” and hand out a sticker, Show you how to disarm people into taking some information.

Behind me I hear you say “don’t break don’t break don’t break the picket line.”

I think, you don’t know what a scab is yet, The ones you know are like shields for healing. Here too they are like shields but instead of stopping blood from overspilling, they stop its warmth from going to the places we need.

Normally you’d be wrapped around me, hiding in my legs but at the strike I struggle to keep track of you, I have to strain to see you.

When I find you, your little chest is puffed out. You are the smallest even though you don’t look it and I scan you for signs of tiredness, hunger, needing to pee.

You don’t look for me at all. You don’t follow me. You want to follow the impossible blue sky that is the weather of your first strike.

On the train to the rally which you beg me to let you go to, you sit close to the other girls who ask you if you have a peanut allergy and feed you more cookies.

But then we enter the swell of people beginning the march and you raise your arms, like my baby, and ask me to carry you.

And I know I can’t bear the weight of you all the way and I know your legs might not last, so I hear myself say “we should go home.” I tell another mum, I want to leave on your high and not risk your low.

An explosion of rage follows, a memory we’ll carry, a record of you demands.

“You stopped me from striking” you tell me,

“stupid mummy I want to go on the march”. I witness this fury - I have known it.

A boiling over of desire - I hold it.

In the station you glue your feet to the ground, you won’t move, you strike here too -me with your fist. We sit together until you feel it's safe to relent and with your last shout, you try one last time -

SUPPORT THE STRIKES

you shout and the family across the platform look at you blankly.

And your lips seal.

From a small opening, you speak, tell me you don’t like how it makes you feel mummy why don’t they call back?I tell you you can’t win them all and you say but why? I say I don’t know, but we move, and you move, and we try.

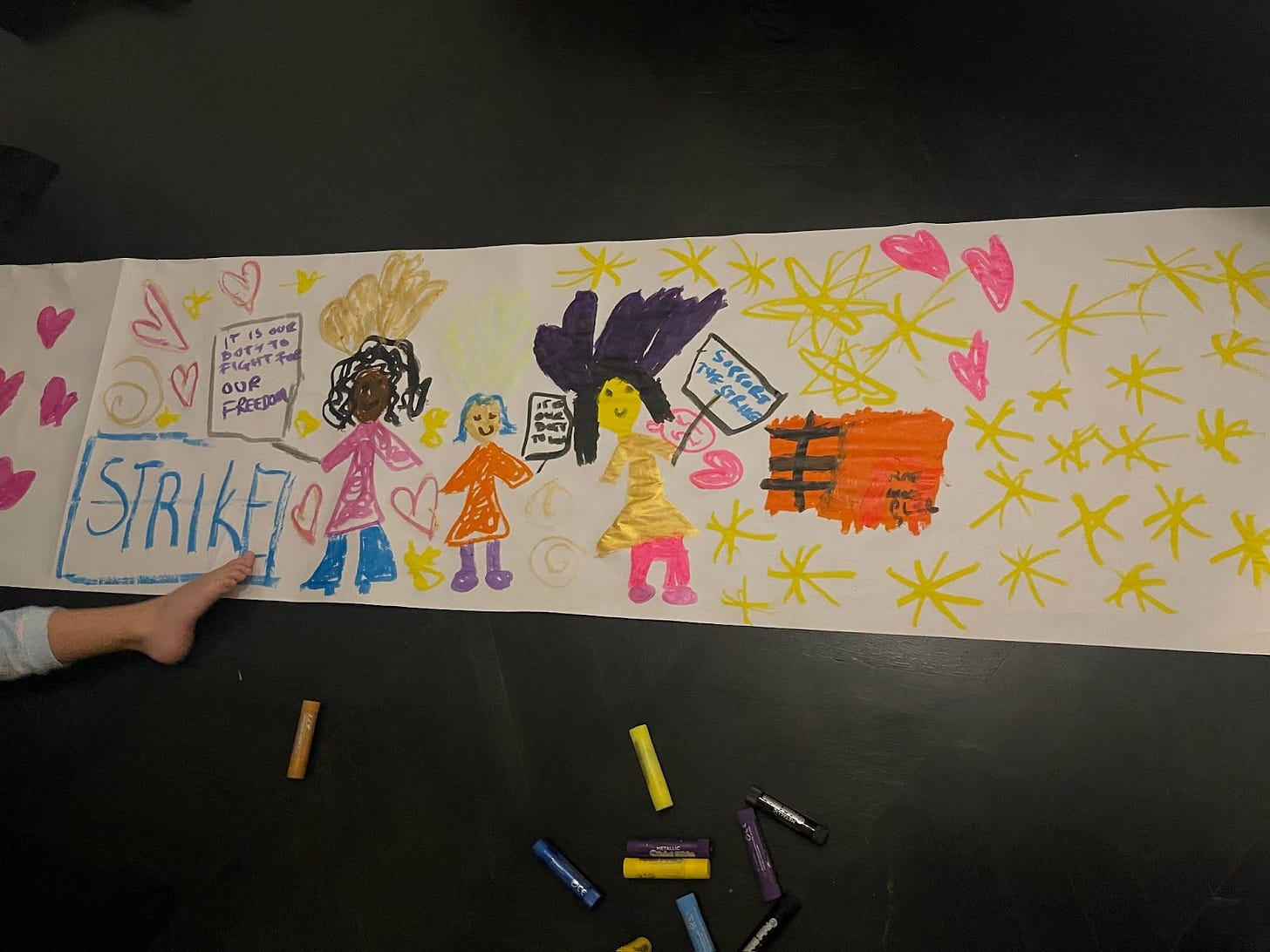

And then after we go home and we unroll a piece of paper

And we strike it with colour.

You draw a line of people and they wear gold and pink and orange. You give them gold crowns and flared trousers and we draw signs. You write Support the Strikes on yours and I write It is our duty to fight for our freedom on mine and then before I can teach you the last line, you have drawn an orange wall and are telling me look mummy its a wall but look mummy here is the door in it and in the final white space around and after the picket line you draw spirals and hearts and 10s and 10s of yellow stars,

explosions of light striking the sky.