Leena has been playing a game recently. “Pretend you can’t see me”, she instructs me, “now pretend you can’t hear me”. There are moments when my acquiescence is too convincing and it unfolds inside her a deep sense of injustice “You’re not listening to me” she says, “you’re not looking at me.” I remind her she told me I can’t see or hear her and she recasts the spell for a moment, “abracadabra, you can see me!” and she is heard and seen as she wishes until the magic words hide her again.

Until I wrote this I didn’t realise that I understood the desire for agency and autonomy inside of this game. Even as an adult not as playful in the art of practice or as practised in the art of play, I could, on a level, relate quite deeply.

Thanks for reading Yearning’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

In January I deactivated my Instagram, feeling in my body that I needed to see and hear less, and shake off the urge to be seen and heard so frequently. Since then a loneliness has enveloped me which I have embraced as a teacher inviting it in as an opportunity to examine my relationship with visibility and recognition.

Last month I went to a Film Festival for the first time in a long time. I had forgotten how Film Festivals made me feel, but my body remembered as soon as I went to pick up my pass. I looked around at the different queues, the different bags, the different ways that people held themselves. My body shrank in anticipation of being invisible here, not important. I wondered, when I had consented to being here, why had the trace of rejection remained but not the memory of choice?

I returned to this thought a lot that week, as I moved in and out of different spaces, different relations. I found moments of peace, new connections, but at times I felt deep disequilibrium, like an alarm that would not turn off. I came back joking about film festival dread, but as I have settled back into my life on my return, I am thinking about it differently.

On a panel I attended, a group of programmers talked about subversion in film programming. The panel took place in Silent Green, a former crematorium, located in Wedding, a part of Berlin that people tell me may or may not be about to be gentrified. The crematorium is a symbol of a practice of resistance - in the face of massive resistance from the established Church, the first cremations in Germany became connected with expressions of progress and secularisation. This history of resistance has transmuted into an art space, set slightly away from the main road, in an imposing building with an excellent restaurant, built to hold “freethinking ideas.”

On an uncluttered and gently lit stage a panel considered a series of questions“How do festival programmers navigate sensitivities in today’s current political climate in which cultural policies and ideologies of nation states often determine what can and cannot be screened? What are some of the strategies, processes and methodologies that curators are adopting to avoid self-censorship so as to continue exhibiting works that redefine cinema and simultaneously critique and challenge the status quo?”

As they moved in and out of their accounts of their attempts to subvert, panellists spoke of positionality and risk. Of course, subversion was in the context in which they worked, some acknowledged, those in Europe or North America faced less they emphasised.

I was reminded of a text that I recently read by Sarah Schulman. In Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, Schulman outlines how the specificities of pre-AIDS rebellious queer culture, cheap rents, and a vibrant downtown arts movement vanished almost overnight to be replaced by gay conservative spokespeople and mainstream consumerism. Revisiting the book more recently she talks about the true qualities of oppositional politics: as rooted in “high risk” living. These artists had been rejected by their families, left to live precariously, vulnerable to arrest for loving one another and formed ways of living and working - sex work, drug taking - congruent with this positionality in relation to respectability. Schulman describes how the lives of many of her friends who she lost were antithetical to ideas of respectable comfort (perhaps because none was ever proffered by a society which demonised and criminalised them) but full of creative subversion, and posits that when this high risk existence was wiped out during the AIDS crisis, what was left was a gentrified politics of acceptance, one where theory became privileged over action and radical activity became confused with deeply ingrained (reformist) normativity.

At one point a panellist shared that when a programme they had been researching ran into legal trouble, they were advised that the most radical thing they could do was to be taken to court. The story was delivered as an interesting anecdote, something almost impossible. “Of course we couldn’t do this” the storyteller seemed to say (and perhaps did, I don’t accurately recall). The friend next to me couldn’t bear it any longer “well you’re not really subversive then are you!” she exclaimed to no one but me and the empty space between the stage and our seats. I squeezed her knee, grateful for her voice, not on stage but next to mine, co regulating to my own bodily reactivity to what was being said on stage.

To subvert is "to raze, destroy, overthrow, undermine, overturn," from Old French subvertir "overthrow, destroy" (13c.), or directly from Latin subvertere "to turn upside down, overturn, overthrow," from sub "under" "to turn, turn back, be turned; convert, transform, translate; be changed"

And although I understood everyone in that room to be able to theorise this, perhaps much more eloquently and academically than I ever could, I wondered about any of our abilities to truly practice it. What would it mean to practicing razing, destroying, overthrowing, undermining, overturning curatorial practices in film? What does it mean to choose risk (the ultimate act of solidarity?) even if it is not chosen for you? I wonder if at its heart, in the context of curatorial work, it would be a question of refusing gentrified visibility - that of the ‘respectable’ programme that adheres to the codes of licensing and rights and results in more opportunities as a curator and critic and embracing one which embodies, on some level more risk and less currency.

A curator from Tehran, spoke of the gaze. I cannot remember her exact words, but I remember how she held her eyes, down or sometimes through the audience. She said something like (again I am interpreting her words rather than accurately transcribing them) “we are always dealing with the gaze, the averted gaze, the dominant gaze, we must disrupt the gaze, enable the gaze”. She talked about the European and North American art worlds’ fetish for the politics of representation, of the centring of what they deemed to the most marginal, a pathological curatorial need to enter into the colonial politics of ‘recognising’. How did this constitute artistic freedom for artists, away from these centres who wanted to make work and be seen on their own terms? She mentioned something I couldn’t understand in the moment. Sharing her sadness that a programme that was presented in solidarity with Iran gave her only two choices - either to take part in the programme or to not. She did not expand on this, but I wondered afterwards, would the ultimate subversive act perhaps have been to realise that this tool that we have in our hands - film and the practices we have designed around it, of curating and programming - cannot really enact solidarity? What if we saw that the repetition of these practices could only interrupt or distract or draw attention but not truly transform our attentiveness? Might we see that there is a way to practice the difference between what one panellist referred to as “quantities and qualities” of visibility?

Could subversion in programming in curation be about a different quality of attention? If instead of providing a closer attention to “the work” (of the choices of the individual artist) we attended more closely to “the work” of the curator, to the limitation and hidden choices in our practices? In this way might they change? In turn might we, and our desires change? And then, perhaps, the world? What if we didn’t attend so closely to the differentiation of the multiple crises we face, but in the repetition between the calcification of the practices we repeatedly employ in our work and the roots of the crises we can choose to face or not face, depending on our positionality, collectively or alone.

***

Later, I sat in a very different setting full of bright lighting and red furniture, wearing a headset as if ready for a Ted Talk. We were here for a panel using very different language, but perhaps rooted in the same limitations of yearning. Here there was less theory but similarly an incapacity for our words to turn into meaningful action. In our need to '“curate the future”, to allow ourselves comfort in something that has been and felt hostile, and not included us in the past, we accept visibility as a currency worth defending. I am asked about my belief that if we truly practised the things we say we want, ethical relations, empathy, solidarity, decolonial film practices, we would not end up with the container of a film festival like the one we were sat in. I feel palpably the energy of being a killjoy in this space, which held the excitement, the passion and the thirst for ‘change’ in an industry that many believe in. I forget that I consented to being visible here as a sense of injustice envelopes me. I want to shout “you are not listening to me!” forgetting that the words I have said don’t have the magical charge of “abracadabra,” partly because I have chosen to sit in a place where only certain desires can be rendered legible.

***

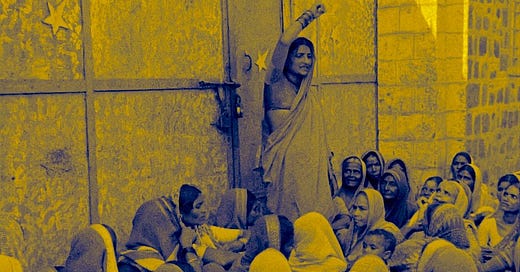

Outside of the festival, I spend some time at SAVVY Contemporary’s new show OUR DAUGHTERS SHALL INHERIT THE WEALTH OF OUR STORIES an exhibition which “performatively unpacks” the practice of the first feminist film collective from India – the Yugantar Film Collective. I turn up there repeatedly to watch films I have already seen, the very antithesis of being at a Film Festival full of new work.

In the conversations held every afternoon, connections are drawn between collective memories, collections and collectivising and the possibilities of film to compress time. How can the immediacy of filming struggles that are still relevant today, be protected and not neutralised through rarefaction? Is it by controlling where they were seen and by whom? Instead of seeing institutions and festivals as benevolent enabling protectors who can provide us opportunities, or even enabling gatekeepers which we can skilfully navigate towards our radical ends, should we take a more straightforward, pragmatic and transactional approach using them for their asymmetrical access to technologies of preservation and historicising? As curators, rather than learning how to be gate openers, linked to other gatekeepers, could we learn how to form what Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa would have called a bridge with our backs, so that works can travel - without the need for our visibility -towards striking workers, unions and collectives for whom the lessons are not theoretical but instructional?

I turn up there to see Deepa Dhanraj speak with her collaborator Nicole Wolf with whom she has worked to restore her works. In one section, Deepa talks about consent as a constant process. In filming the women’s movement in India, she recounted the need to navigate not just what was said but how it was said. To care for the ways that the people who she made films with wanted to say to what they said, and not to centre how she wanted to hear it. In the moment I think about programming as a constant act of consent too. How to show films in ways congruent to the ways that they were made, not in the ways that we want them to be seen, so that we can be seen and heard in a certain way? Writing these words now I wonder how I can practise that for myself. To craft words in the ways that I want to say them, show myself in the ways I want to be seen, letting go of how they might be heard and how I might be seen, forgotten or ignored.

****

In a text called Cultivating the Self: Embodied Transformation for Artists Alta Starr writes: “it takes 300 repetitions of a movement … to build muscle memory, and 3000 for that move to become embodied, or second nature, consistent and reliable….I’d argue that the competencies (or capacities) we want to embody in our lives, in our leadership, teaching, and art-making, are far more complex, and require even more repetitions.”

I see my movement in and out of the spaces that leave me feeling unseen and unheard as an embodied repetition. It is a repetition for which I am rewarded constantly, with invitations to speak, with the serotonin of a like or a share, with (some) money and the promise of visibility and status. What might happen if I become more aware of these repetitions as choices disconnected from their promises of the currency of visibility and more immediately connected to the unpleasant physical sensations and politically passive energetic exchanges I have to inure myself to? Might I notice the times where I might not be rewarded in the same way, but I might feel completely differently?

I come back from Berlin the week after and deliver a reading for a strike fundraiser organised by Abeera Khan and Lola Olufemi. I write and read a piece about taking. Leena to her first strikes, the erasures of histories of protest in my local area, about the possibilities and impossibilities of thinking and being outside of gentrification. Others read about love, about anger, grief and sadness, about organising, about joy and friendship. The stage set up is minimal, but everyone on stage is bathed in light so completely, so that they are totally seen. Each person’s voice is so clear, so true to them. Here it is easy for one night of reading, laughing and dancing, to imagine a space of political solidarity that can hold simultaneity where multiple strategies are attempted, understood and held.

There is a stage but the audience isn’t an audience or a passive spectator, they are callers, responders, a chorus. The platform cannot interrupt our relation, it just helps us to uplift the person who has spoken, who has dug deep and who has tried to resist.

I’ll tell you more about it next time.