Notes on insufficiency (ON FRICTION AND THE UNDERTAKING OF THE PEARL)

Versions of these words have been spoken at IDA, SAVVY Contemporary and an IDFA convening. Here they are offered with new inserts.

I

A prayer.

I want to begin with a prayer that contains the words of many others, may our words witness each other, merge into one prayer for each other.

Hold yourself in any way that you feel best called to. Eyes down or raised to the sky closed or open. Clasp your hands together, at your heart, hold your neighbour’s hand, support their back.

I offer a prayer for my integrity.

For my implication in inequitable labour conditions and genocide everywhere. Not a prayer to absolve me, a prayer to hold me in the intention of attention. Of all that is enfolded in that attention, of the tension, of the tenderness.

I share this prayer as an invitation for you to hold me in this intention. Attend to me, be tender with me, hold the tension with me.

A prayer for these words written on my computer. My hands free to type into abstractions, poetics, reflections, on materials handled and provided to to by communities and hands that are forced into dangerous labor conditions and threatened by militias for the sake of the tech industry and our own consumption patterns. May we all correct our own patterns and adopt solidarity, may we understand the power within us to make the necessary changes to our behaviours, and may we learn and understand the interconnectedness of the peoples’ plights and our roles in them, so that we can tear down the powers that be.1

A prayer for my presence with you as I perform my questionable, insufficient labour for you, with you. Let it be a prayer also for your presence with me as we make these moments together. Let us be committed to qualities of softness, let us relinquish toughness. Let us handle each other with gentleness over harshness let us hear each other’s words with openness over assumption.2 Let us let each other rest, let us under rather than overstand. Let us practise care over cynicism.

Let us let that fill out our collective body.

Yet let us not use any of the above to be naive or to avoid the necessary risks of speaking out, speaking firmly, speaking clearly.

A prayer for the insufficiency of cultural labour as I know it. The ways I cannot measure up to my own ideological aspirations. Every time I speak and am invited to speak let me refuse even as I accept exceptionalism. Let me always question why I should speak, interrogate the intentions of those who decide or conclude that I am the voice that should be heard.

A prayer for my obliteration, for the root of that word, the absence of my words.3 A prayer for what I see when I write/ speak that word during multiple genocides funded by my taxes and therefore by my artistic labour - the absence of life. A prayer for the way words turn to rubble in my mouth again and again, a prayer for the way more rubble appears before my eyes.

Open your eyes.

II

A letter.

Dear Mokia, Abhishek, Billy,

Thank you for inviting me to write to you about my impressions on what shape Labo*r4 has taken, inside the shapes in which it was conceived.

I want to frame, perhaps pointlessly, perhaps insufficiently perhaps naively that I do not speak here to and from the overarching idea of culture as crafted institutional engagement.

I write to you in a letter like this because I do not have a critique, or argument, I can only perform my questions. Everything is offered in the form of call and response or perhaps mutual aid; a polyvocal political participation open for dissent and disregard. The form I offer you is the only form I feel worth salvaging during this time - a form of relation in gathering, of taking responsibility for each other’s ambivalence, of each other’s hypocrisy, not by symbolic acts or putting pressure on higher ups or authority figures, but through the act of making something new (poesis) and being together (sympoesis); of making meaning together, of building new social relations in cultural work that feel (will be) more survivable.

In the words of Mariame Kaba “everything worthwhile is done with other people.”

Here is the rubble in my mouth again.

{I am speaking in a room full of industry people. My voice will not stop shaking. I have said the words before, I have been invited to speak. My voice gargles in my throat, the pitch unconvincing: not just a tremble but a constant shake. After I stop speaking, they thank me for my emotion, then they tell me, in their liberal code, that the connections I have followed flow from my position of privilege. I would have followed different connections if I had experienced true risk. In this is both a truth and a threat. In this moment the trembling stops: I meet the danger that my body had sensed, a translation of what they had wished on me}.

At its source, Ground Provisions is a reading camp. We do many things together. We write, we organise with others, we make movies, work with artists and curate music and film. We travel the Afro-Asian century. We work in the Caribbean and we work in Asia. But if we were to return to the source, this source would be our reading camp. We conceived of the reading camp as a kind of refuge where people can read together. We use the word refuge because the camp involves reading in a quiet place, a place of contemplation and reflection. We read together and to each other and by reading together we make this refuge a place of conversation, discussion and conviviality. It’s a retreat, but one we make together. And this is why we call it a refuge. We retreat together. We read together. We read to each other. When we offer a reading residency at our base in Barbados, we offer it to read together.5

III

A Question

When I was invited to speak, I was humbled and into this humility questions tumbled. What did it mean to place my work in the lineage that is offered in this exhibition? How could I, schooled in the gentrified spaces of the university, finished in legacy cultural institutions against which much of my ‘activism’ emerges, engage meaningfully with this legacy. I sat with your question which emerges from your engagement and offering of Medu Ensemble at this time:

If we see culture as a weapon of struggle against apartheid, imperialism, patriarchy and other dominant ideologies, how do we understand the role of the cultural worker?

But of course the social reproduction of ‘our thing’ in general, the life-giving arts, care, culture and cultivation perpetually risk being called partial, incomplete, in need of the masculine energies of ‘proper’ politics, ‘active’ resistance, of policies and strategies. The same is true of reading and studying when they are only understood as the support for something else, rather than the life-giving arts themselves, rather than as a vital part of our thing. Indeed some might say our slow reading is not urgent enough given the state of the ‘world’. But travels in the Afro-Asian century teach us otherwise. Amílcar Cabral never minimised these arts, nor Qiu Jin, nor Claudia Jones. Jones did not start Notting Hill’s carnival because she gave up on politics. Nor did the Black Panthers think of these life-giving arts as only support systems. Some say the Panthers started as a study group. And this is true, but they did not start as a study group because they wanted to be included in the university. They started as a study group because they saw the impossibility of the university, and the need for something else. Study was at the heart of their revolutionary practice, not a preface to it, as in so much scholarship in the university today. Such was equally the case among the many anti-colonial movements we try to visit in our travels through the Afro-Asian century. Malaka was said to have gone before the Comintern to try to convince them to take Islam seriously as part of the life-giving arts. They thought he was talking about organising tactics and refused his request. But he was urging them to see the study going on in front of them, in Indonesia and elsewhere, urging them to see that communism and Islam could read slow together, that this could be our thing.

I answer your question with another, one that I have been taught by the most influential of my teachers as the most simplified distillation of unlearning that we can offer ourselves at the point of coming to know how we have been shaped by forces outside of ourselves:

Who or what put that thought there?

IV

On Love and Hate

In the meeting of question with question, I am not trying to detract, I want to go deeper with you, I believe in James Baldwin’s formation that “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” Questions and questioning is one way we can go deeper together.

We know as people who have experienced being students and teachers in the university that despite the fact that we have become used to forsaking reading together, discussions in the classroom can generate something special. We can feel each other’s energies, lose ourselves in the conversation, feel the presence of something in the room. In these moments, we begin to lose our individual status as producers and feel our common materials and our common and differentiated materiality. And then we have to be graded or to give out grades, and we have to graduate or consider the class completed. The collective product in the room (which is firstly us) gets divided again into marks, rankings, metrics. We get divided away from what we have become together in the room. Even most teachers today get marked and ranked. In other words, our lives together in the classroom get individuated at the end of our experience. But the outsourcing of reading means we are all too ready for this. After all, we came into the class ‘by ourselves’ through this piecemeal work of reading. And everyone has experienced the collective spell being broken by someone shamed for not reading, whose secret is exposed, or someone, who like a good consultant disrupts the collectivity but claims to have secretly read more. Thus, Ground Provisions reading camp is conceived in the first instance to allow us to read together, in each other’s presence, even if we are in a corner of the yard while someone else is on the porch. Even if reading together is only a feel, we dwell in together.

I want to tell you that since October 7th, perhaps before that but certainly then, I began to hate art and the spaces that it circulates in. I do not know what it means to make work, to care about circulating it, to care about receiving it. I hate the structures around it. I hate the self satisfied spectacle that erases everything I have been feeling carrying and raging with and against.

Every time I go anywhere or attend any event I wonder if everyone else is placing what they see and feel against what I have seen and felt. I wonder if other people who make art and go see it have also seen images of bodies, emaciated, flattened, dismembered, forgotten, tortured, strewn, scooped up with hands into plastic bags, gathered into shrouds and embraced, tended to, or still buried deep within rubble. I wonder if they think, like I do, about white phosphorus and how its burns cause cylindrical spaces inside bodies where there was once flesh.

I wonder if they too have spent nights wondering where those chunks of flesh go.

I wonder if they heard the voice note of a medical aid Palestine worker who said that there is more spilled blood in Gaza, than drinkable water.

I wonder if they have seen the decapitated children, the one with the contents of her head somewhere else, the amputated toddler, the blown apart bodies, the girl hanging from the side of the building, the one who had begged her mother to go out that morning, who was allowed freedom from her mother, despite her mother’s fear, and who was later dragged into the emergency room, dead, still with her rollerskates on.

I wonder if everyone else’s life is falling apart, their belief in everything convulsing? I wonder if everyone else is as less sure of the whole, has everyone else felt, even if they have not read Franz Fanon’s words: “Decolonization never takes place unnoticed, for it influences individuals and modifies them fundamentally.”

I do not tell anyone what I think, not directly. The gap between what I have seen and what I have shared testifies in some ways to the ways that I as a cultural worker - safe from the sharp end of present day settler colonial violence - am immersed in a materiality that cannot let in the full realness of this moment.

Have you read like everyone says they have read Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang’s “Decolonisation is not a metaphor?” In it they write, “there are parts of the decolonisation project that are not easily absorbed by human rights or civil rights based approaches to educational equity.” Such approaches structure the ethical framework of much of the work of formalised cultural production and theorising that we are part of. This letter is inevitably part of this ethical framework. Even if in my formal choices I decide to speak not as an artist delivering critique, or an educator or activist trying to change hearts and minds but shape shift my mode of address and ethics into the possibility of writing to a friend or an ancestor, still its affective charge skirts around the reality of resistance, pushes back at attempts to grapple with what Steve Salaita has called a “practical appraisal” of violence.6

There are words that are useful for them and not for us.7 Feel the word genocide in your mouth. Offer it to them, see what they do. Watch them shove it back down your throat.

Feel the word Nakba (catastrophe). Pass it around those who already know. See how they hold it, feel the space in your mouth.8

V

On Violence

As a student of abolition, I have been taught to take violence seriously. As a student of this moment, I ask myself, if to be a martyr is to witness true acts of faith, then what are we when we witness the full insufficiencies of our work in culture?

But there is a second immediate source for the reading camp, and that is the (undercommon of the) concept of study itself. Stefano has been speaking of the concept of study with Fred Moten for many years now, and practising it in what might be called ‘visitations’ with Fred when they are invited to spend time with students or artists or community workers somewhere. And all of us have been discussing and practising it together. And these visitations have some of the quality of bearing witness and of prophecy. Fred and Stefano do arrive with ‘the good word’ but only because they know people already have it. And what they already have is study, and study is what they call a base faith, a material practice, mysticism in the flesh. Study is what we do when we come together on our own terms, rather than theirs. It is as Fred and Stefano said in an interview, ‘talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice’.1 And we should add here also: reading together, maybe in silence, or laughter, or occasional comment, or restlessness or stillness, but together. Anyone who has read with a kid knows that authority breaks down. Kids are said not to read as well as adults but it turns out kids have interpretations and these readings can make the adult readings partial and incomplete. But this is true for all reading together. Reading together makes us incomplete together, and partial towards each other, for each other.

{Robin D G Kelley speaks about catastrophe (Nakba) and emergence.9 He tells us that abolition is not the same as revolution. Every uprising contains omissions. Abolition demands the reordering of things, it is against normativity. I cannot be an abolitionist, I can follow the connections that abolition offers me. Abolition invites the following of connection. The only thing that stops us is our own fears, is each other.}

VI

On performance.

Just before you asked me to speak, I had some conversations about performance.

M told me that performance is not acting - it is not pretence; it is not mannered. Performance is completing an action.

J tells me she uses performance to face fears.

I am reminded when M speaks of Sara Ahmed’s work on diversity policy and its non performance.

I am reminded of the opening to Solmaz Sharif “The Near Transitive Properties of the Political and Poetical: Erasure”

Every poem is an action.

Every action is political.

Every poem is political.

The exhibition you’ve asked me to perform in is a project anchored in the work of the Medu Art Ensemble, which was active in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa from 1976 to 1985. The Ensemble intentionally rejected the classification of their position as “artists”, seeing a need to transcend the elitism of the term and choosing instead to ground their practice as “cultural workers.”

I think about the actions they might have wanted to complete, which ones they might have dismissed as non-performance: not poetic, not poesis, not sympoesis.

I think about the fears that they wanted to face. Have I ever come close to such fear?

I am trying to complete an action.

(For whom, to what end?)

I do not know.

After Fargo Nissi Tbakhi I say:

Let me strike from this performance.

Strike Germany.

Let the poem rest.

Language is a failed state. 10

VII

On being an artist.

Being invited to speak on a stage as an artist makes theorising easy and reality abstracted; no one asks artists to speak on Palestine, and artists are doubtful of what their speaking can do, for what end, but I, who claim to be an artist, have chosen to speak about integrity and so I cannot speak about anything but Palestine.

Integrity has three meanings - one pertains to honesty; the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles. The second is one of being unbroken; the state of being whole and undivided. The third is the condition of many parts together being in synthesis; to be unified and sound in construction. In the last months more than ever it is clear how little integrity in any sense of the word cultural work or the world around artists, can claim in its current infrastructures.

A friend and fellow cultural worker Sonya Childress teaches me that there are three points of contention in cultural work in the present: Authorship, Accountability and Ownership. These three points of contention are present in my engagement with Medu Arts Ensemble too.

Archival documents “are not items of a completed past, but rather active elements of a present,” writes Ariella Azoulay.

How not to engage with the archival record they leave us as you tried not to, as Fanon warned not to, how to avoid engaging with them as “mummified fragments which hypnotise us”.

How at the same time can we understand authorship, ownership and accountability in our engagement with an archival record that seduces us with its political desires?

If the artist is a lover who comes to show us what we do not want to see, then when the artist enters the archive, or is entered into it, where is desire and who owns, and generates it? Who is accountable to their desires, yours, ours?11

And there is more to say about refuge and visitation, and about reading, in the practices of Ground Provisions….There is the question of how we keep ‘their thing’ going, and the question of how we keep ‘our thing’ going. ….To find refuge is to find the arts, be taken into them. To find refuge to read then is to find these arts aimed towards the support of reading together. But it is also to return reading from its outsourcing to its home in these arts, which is to say to return study to its home, where it has always been, and always been on the run, fugitive.

VIII

On stakes.

I am reading here, on this platform with freedom to use my voice, as a non-Palestinian, as a non-German and a holder of a British passport.

I stand here as a product of British colonialism — my family history encompasses the complications of this ancestral history; marginalisation, racialisation but also implication in the political ideology of Hindutva, which like Zionism roots its aims in “resettlement, reoccupation, and reinhabitation that furthers settler colonialism.” I stand here also as the mother to a daughter who has German citizenship and ancestry. A daughter whose ears are covered at this moment so that she does not have to engage with the reality of this moment.

So that she can remain a child.

With this history at my back, if I pay close attention to everything I can feel at the centre of my being, I can feel the imprint of a heel on my face, even as I am aware of my own being pressed on the face of another.

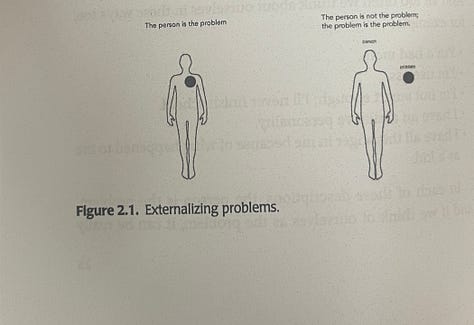

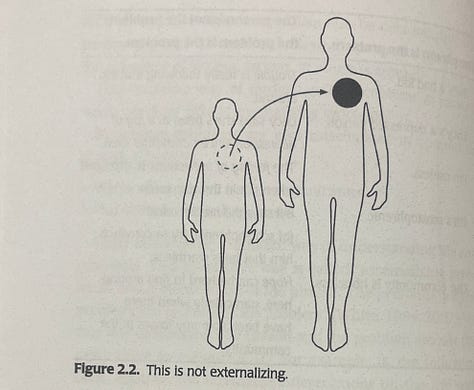

{We are walking down the street one afternoon. I am angry. She is angry too. We cannot meet each other. She shouts back words I have taught her, ones she has made her own, for her own ends. She makes me see them again, makes me realise I had just said them in one place, failed to enact them in another. “Mummy I am not the problem. THE PROBLEM IS THE PROBLEM”}

IX

On incommensurability

Ursula K Guin wrote ‘You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.’

As I write to you, I want to tell you that I think Le Guin’s words relate to Tuck and Wang’s ethical framework of “incommensurability” and in connecting these two fragments, I want to put words to something many of us have felt - that what we have all witnessed in the last 11 months has underlined something we already knew and now can no longer ignore — that the tools and systems we have to organise ourselves, our work and our desires are aligned with and implicated in systems of power that are complicit in this genocide even if we vow that we, and our work is not.

As these systems violently reassert themselves even as the bloody violence that props them up is revealed and disavowed, again and again, many of us wonder if our ongoing political commitments could ever align with the current ways that we are permitted (and permit ourselves) to make.

X

Playing the tape.

During such a time, have you also found it hard not to collapse into the jaws of nihilism, to feel that nothing matters? Have you fallen prey to busy work, organised around the existing architecture of spectacle in which our work sits? Have you also insisted on their possibilities even as time and again we are shown that what happens on stages, screens and spaces we have dedicated ourselves to creating cannot affirm the life we seek to affirm?

All the while have you noticed how integrity, or the search for it, in itself becomes a privilege - another measure by which to dehumanise others? These ‘others’ are not those who refuse it, (which would be accountability) but are those to whom it is refused — the ultimate abstracted evasion of human responsibility.

In the words of Muhammad El-Kurd:

“Distracting questions—[ in our field about open letters, who has or will sign them, where history must begin, who wears a pin to the awards, who boycotts, or does not, who uses their platform to speak]—feed the discursive loop that prioritizes a conjectural “day after” over the material present. But here, in the present, there are more pressing questions: What are the mental and muscular consequences of being forced to transform a taxi into a hearse? What becomes of the nurse whose shift is interrupted by the arrival of her husband’s corpse on a stretcher? What about the father carrying what remains of his son in two separate plastic bags? What happens to him after all of this death, once he is alone and away from the cameras? What kind of man will the boy carrying his brother’s limbs in a bag grow up to be?”

Or as he wrote in poetry in 2021

"I've been meaning to eat today / but I spent a thousand mornings since sunrise / insisting upon my integrity."

What El-kurd witnesses for himself and his people is that what we are constituted of is not what the nation-state and its structures of knowing says is real but from the knowledge production of our spirits and what we feel to be real.

We are our perceptions, our senses, our sense making which happens through our bodies, and through our experiences of the world, and of each other.

We are all, artists or not, cultural workers or not, implicated in making the real for each other.

At a time that not just of endless image circulation, but also statement making and liberal equivocation which continuously changes the points at which the real is constituted, it is hard to believe in the vitality of language. I wonder if the thing that has killed language at this moment is its mobilisation in the project of linearity, the constant reliance on meaning making through that which is countable and measurable. In this, is the denial of simultaneity; of the temporal, sensorial and embodied dimensions in which language exists.

This is the space where the image re-enters.

In recovery, therapists often speak of playing the tape all the way through to keep us attached to being accountable to our actions and choices. I wonder what the tape will show when the statements we have signed in these past months are found in the archives? Will it show we organised around the centre and dignity of our creative instincts, what we knew deep down to be true about how inherited narratives can be constructed and remade for new ends, or around an old concession which we were told was reasonable?

During these months of letter signing, I wonder if the souls of those of us convinced we are concerned with the real will survive our need to concern ourselves with the fiction of the nation state; having become embroiled, sometimes against our better judgement, in the performance of condemning, conceding, appeasing in the hope of mobilising across difference.

XI

On form and formal choices

In this compromised hope (which is in fact the invisible infrastructure of respectability which is the respectable - professional, crafted, insider - shape of cultural work), have we forgotten the determination of form (which is in fact our autonomy in deciding how and why we connect with each other through this work)?

All of our efforts with the reading camp, with visitation and refuge, travelling through the Afro-Asian century offer us the chance to take a different position towards the art we curate, the art we make and the art we organise with others. For us, reading is a condition of making, reading together is a condition of making together. …. We think that making reading visible, making reading together visible, helps to keep the making visible too. It helps us to see what is made through a vision and a feel for where and how it was made together. We can slow down in what we see, hear, feel, touch in this making. We can both recall and foretell the slow reading that makes possible the continuation of this making. We are reminded – during a visitation – by our friend, Amaryah Jones-Armstrong, a young scholar of black liberation theology, that one of the roots of ‘slow reading’ is in Jewish religious reading practices of keeping the text bodily, keeping it among us. This is opposed to a ‘close reading’ that suggests very careful examination can yield a transcendent meaning from within the text. Our reading is slow because we read together not to master the reading but to unlearn each time what we know. We don’t study to graduate, to get credit, to finish. We study to help each other get incompletes. We study to go into debt with each other. We read slow to let things fall apart, to help each other fall apart, to hold each as we fall apart. This means in turn that when we make, curate and organise art we are not culminating our practice, finishing our projects. We are slow reading, we are studying with others by other means. Our art practice is an extension of our reading practice, as coming from and returning to the sources, as a temporary emanation of our groundations, our base arts of being together by reading together. And what we make under these conditions also has to come back to us, come back into study after it is made, or else it will lose its groundations in our social reproduction and join the machine.

Formal choices in our art-making are intentional, we take differences seriously when we make formal choices, those who make work that pushes against established norms, know that flattening the form of our making flattens what can be said even if it means it can be said to more people. So how can we take form seriously when we assemble our demands as artists and cultural workers against genocide that needs all of us to resist?

Journalists from Gaza filming from within their experiences have generated a reality that western media would dismiss as partisan, truths that feel as if they should be fiction and conjured poetry from the deep well of knowing that their experiences contain. There is nothing I have seen that is more spiritually true than the image of a man cradling his dead grandchild and speaking to her as if she were alive, gently telling her "you are alive and as beautiful as the moon” ''you are the soul of my soul'.

Nothing has more challenged the reality formed through the affective distance of western journalism and its form of the real, of truth itself, than this image of a man’s tender, poetic attempt at the retrieval of the impossible to retrieve. In this attempt at poetic fiction, he recovers for himself, a documentary humanity from those that would (and have) taken it from him and others like him.13

If testimony and poetry live so closely in order to defend life where there is so much violence then what is the use of the formal distinctions between them anymore?

XII

An artists search for integrity

In his speech from 1962 called the artist’s search for integrity, James Baldwin begins with the introduction of the idea that the integrity of an artist is an analogue for the integrity of aliveness - of being human. In it he reclaims the utility of language and story as guide for practice even as he affirms their emptiness as simple theory:

I really don’t like words like “artist” or “integrity” or “courage” or “nobility.” I have a kind of distrust of all those words because I don’t really know what they mean, any more than I really know what such words as “democracy” or “peace” or “peace-loving” or “warlike” or “integration” mean. And yet one is compelled to recognize that all these imprecise words are attempts made by us all to get to something which is real and which lives behind the words. Whether I like it or not, for example, and no matter what I call myself, I suppose the only word for me, when the chips are down, is that I am an artist. There is such a thing. There is such a thing as integrity. Some people are noble. There is such a thing as courage. The terrible thing is that the reality behind these words depends ultimately on what the human being (meaning every single one of us) believes to be real. The terrible thing is that the reality behind all these words depends on choices one has got to make, for ever and ever and ever, every day.

The intentional practice of choice is the first thing we disavow when we give up our integrity. Choice disappears or at least seems to when we are constricted or when old choices are no longer available or when scarcity becomes the predominant narrative, when our work becomes what Audre Lorde called a “travesty of necessities”14 and not a means to affirm life.

This distinction between ascetic necessity and abundant affirmation in our field is presented as an issue of scarce resources, and plentiful risk, but what if this distinction were an intentional act of warfare on our imaginations repackaged as necessary collateral damage?

What I mean is, if as is often said that Palestine is really freeing us then how do we articulate that process in the now, in the contexts in which we work? Or as Gargi Bhattacharya, scholar of racial capitalism who has also written about political heartbreak writes: “Palestinians in their liberation struggle reveal the fictions of our freedom. The reach of occupation and forces that further that occupation”15

When I extend her words, I understand that what they mean for me, for us, is that the limits of our ability to engage with the issue of Palestine — embroiled as it is in an intersection of violences, from settler colonialism, to imperialism, to state violence to racism, labour struggles and more — is a litmus test for the limits of our desires for the transformation of our conditions; working and living, shared and distinct, always interdependent.

{Not all revolutions are a single turn}

XIII

Omar Sakr writes: There is no bravery in witness, only in resistance

Decolonial theorists teach us about imperial power’s force on the very conception of the human: that the intersections of race, location, and time together inform what it means to exist. Do we believe in the confronting, unsettling truth and dignity of human resistance as a form of aliveness or the more respectable, comforting fiction of human ‘resilience’ with neatly hidden scars?

By the act of witnessing a story, a subject, we enter into a relationship that might avow or disavow someone’s realness. The belief in being real and the power to confer that to others is a gesture of shared humanity; taking it away from someone is an act of profound soul loss.

Who can forget the tiktoks of Israeli Occupation Force soldiers with their trophies looted from Palestinian homes, of young Israeli women donning comical make up to mock Palestinian suffering. Of the Two Nice Jewish Boys imagining a button to wipe out the Palestinians who remind them of what they have stolen. Who can forget the children rounded up outside Al-Shifa hospital, later to be razed to the ground amongst a litany of war crimes, to take part in a press conference to declare their humanity not in their mother tongue, but that of their original colonisers - mobilising an English translation that might somehow render them human enough to live.

{Sometimes the shape of repudiation is a spiral}

XIV

An unsettling truth

When we are attached to truths which are also fictions, they grow appendages, infrastructures and systems of rules which in turn become recognized as regulating our actions, enforced by the imposition of relational penalties.

You know as cultural workers interested in what culture can do in the world, as well as what it can produce, we know that works and and their effects are made up of more than the people inside them, they are made up also of a series of possibilities which are also built by material and ephemeral and sensorial constraints: how much money, how many people but also how much light, how much motion space, time and sound will we choose, in what form, to what emotional end?

Similarly, the spaces in which we gather to share this work - SAVVY being one itself - are built on similar constraints, towards certain aims. The gift of public funding contorts into the acceptance of an act of self harm when located within the context of a nation state implicated in colonialism and its continuities.

This continuity in turn contorts the desire that might have led us to this space - a desire to examine the reality of colonialism and the impulse to free our minds and spirits and material reality from it is presented back to us as a racist act in itself.

What is lost to the most fundamental element of human connection – relation - not just to each other, but to our very sense of of ourselves, our reality when we exploit, submit to and asymmetrically award according to the inherited logics of such structures?

What does it mean to choose truth at a time where it seems we are being told constantly that there is no choice and that everything is lies? When the invisible choices we have made for so long have become faster than thought, so they are buried deep in our passive actions, or inaction, buried deep in the gestures we make or do not make?

How is cultural work as we know it the process of hiding that assemblage, hiding that our process is rooted not in product or discourse but in relation, and that this relation happens not only in a system of sentimentalised collaboration but also in a system of power, deference and appeasement?

XV

A Loophole

Early on in November, as winter set in, I spent weeks obsessively thinking and dreaming about constriction and enclosure. About people trapped in buildings, under rubble, of words stuffed down throats, eyes averted, connections strained.

This suffocation was both real and imagined, a sensorial reaction to what I witnessed from afar and its effect, or lack of, on those around me. I was reminded of this claustrophobia recently as a video circulated of a 7-year-old boy who remained under the rubble for 9 days.

Already starving his tiny body was almost all bones yet he was retrieved, still alive.

The video was shared to affirm the truth of life in the midst of the truth of genocide, “I see no one sharing” the tweet said, “If he were dead, everyone would share!”

I watched this video, and thought of all the will to live, the child’s, the hands around him, that constituted the reality and the image I received.

I thought back to Simone Leigh’s Black feminist convening in the summer of 2022, called the Loophole of a retreat. The loophole is a conceptual framework borrowed from Harriet Jacobs, a formerly enslaved woman who, for seven years after her escape, lived in a crawlspace she described as a “loophole of retreat.” “Jacobs claimed this site as simultaneously an enclosure and a space for enacting practices of freedom—practices of thinking, planning, writing, and imagining new forms of freedom.”16 Or as Ruth Wilson Gilmore tells us: “where life is precious, life is precious”

Reading together, silently or aloud, belongs with dancing together, cooking together, drinking together, watching movies together, building and cultivating together – and making together. Rather than understanding making as the result of successful social reproduction, we practise it as a temporary emanation, a stepping out without stepping away, where art remains part of the life-giving arts, not a superior comment on them or achievement based on their reproductive support. Support is our thing, as Shannon Jackson might say. Support is as Fania and Angela Davis say, the process of creating the society we want right now.

XVI

I said I loved you.

Historian Marina Magloire writes:

Until 1982, Jordan and Lorde were warm acquaintances, as well as colleagues and interlocutors; they shared political alignment on many issues relating to race and gender. But Jordan’s last written words to Lorde, after an extensive epistolary disagreement over Zionism, were “You have behaved in a wrong and cowardly fashion. That is your responsibility. May you […] live well with that.”17

June Jordan also wrote

Intifada Incantation: Poem #8 for b.b.L.

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED

GENOCIDE TO STOP

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED AFFIRMATIVE

ACTION AND REACTION

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED MUSIC

OUT THE WINDOWS

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED

NOBODY THIRST AND NOBODY

NOBODY COLD

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED I WANTED

JUSTICE UNDER MY NOSE

I SAID I LOVED YOU AND I WANTED

BOUNDARIES TO DISAPPEAR

I WANTED

NOBODY ROLL BACK THE TREES!

I WANTED

NOBODY TAKE AWAY DAYBREAK!

I WANTED

NOBODY FREEZE ALL THE PEOPLE ON THEIR

KNEES!

I WANTED YOU

I WANTED YOUR KISS ON THE SKIN OF MY SOUL

AND NOW YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I STAND

DESPITE THE TRILLION TREACHERIES OF SAND

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I HOLD THE LONGING

OF THE WINTER IN MY HAND

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I COMMIT

TO FRICTION AND THE UNDERTAKING

OF THE PEARL

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME

AND I HAVE BEGUN

I BEGIN TO BELIEVE MAYBE

MAYBE YOU DO

I AM TASTING MYSELF

IN THE MOUTH OF THE SUN

All my love,

Jemma

x

Nehad Khader “Director’s Welcome” in BSFF24 Programme Guide https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:EU:319bc09d-82c4-4a3b-8c4b-c87b51628c4b

https://x.com/chenchenwrites/status/1812473944538058900

Solmaz Sharif “The Near Transitive Properties of the Political and Poetical: Erasure” (The Volta, 2013)

https://savvy-contemporary.com/en/projects/2024/labor/

The inserted texts in italics are all from Tonika Sealy Thompson and Stefano Harney’s Ground Provisions. You can read the full text here. https://jupiterwoods.com/uploads/_files/Ground-Provisions-by-Tonika-Sealy-Thompson-and-Stefano-Harney.pdf

https://stevesalaita.com/a-practical-appraisal-of-palestinian-violence/

https://momus.ca/podcast/fargo-nissim-tbakhi/

https://columbialawreview.org/content/toward-nakba-as-a-legal-concept/

https://www.conwayhall.org.uk/whats-on/event/stuart-hall-autumn-keynote-catastrophe-and-emergence/

https://proteanmag.com/2023/12/08/notes-on-craft-writing-in-the-hour-of-genocide/

https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/on-the-record-barbara-smith-on-palestine-june-jordan-audre-lorde-and-adrienne-rich

From Retelling the Stories of Our Lives: Everyday Narrative Therapy to Draw Inspiration and Transform Experience David Denborough 2014. The diagrams were inspired bu the work of Palestinian narrative therapists at the Treatment and Rehabilitation Centre for victims of torture.

See “Open letter from former Guantanamo prisoners to film-makers behind Jihad Rehab,” CAGE International, July 26, 2022. https://www.cage.ngo/articles/open-letter-from-former-guantanamo-prisoners-to-film-makers-behind-jihad-rehab.

Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic,” Sister Outsider (Ten Speed Press, 1984, 2007), p. 55.

See https://x.com/Gargi_at_home/status/1722909444328087997?s=20.

Quoted from the online description of Loophole of Retreat, 2022 Venice Biennale, Oct. 7–9, 2022. https://simoneleighvenice2022.org/loophole-of-retreat/.

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/moving-towards-life/ cf https://www.blackwomenradicals.com/blog-feed/on-the-record-barbara-smith-on-palestine-june-jordan-audre-lorde-and-adrienne-rich “Aisha K. Finch offers one definition of Black feminism and the politics of care that states: “[a]t its core, care is ‘painstaking or watchful attention.” How can scholars pay “painstaking or watchful attention” to not only the richness of the archive but also to those with living memories? Where is the care and concern of “...centering Black life and living” – and in this case, the lives and memories of Black feminists – if they are living and are not asked about their experiences as breathing archives? Are we muting and silencing Black feminists if we only rely on the archives to speak, and do not offer (or even consider) the opportunity for Black feminists who are still with us to speak for themselves?”